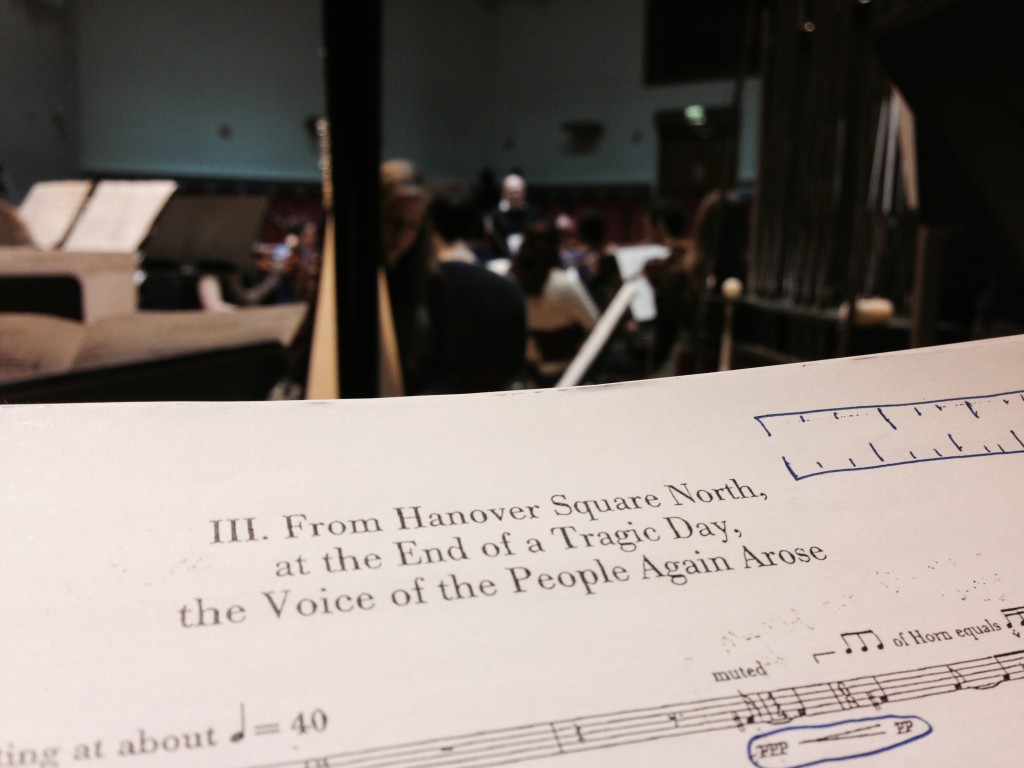

Tonight I will be a second conductor in a rare performance of Charles Ives’s Second Orchestral Set, by the University of York Chamber Orchestra and first conductor John Stringer. I will conduct in the third movement a “Distant Choir” instrumental group, playing at a slower tempo than the main orchestra: the Distant Choir is in 3, fitting within the bars of the main orchestra who play in 4.

The whole work brims with quotations from American culture of the time to depict particular scenes, not least in the third movement: “From Hanover Square North, at the End of a Tragic Day, the Voice of the People Again Arose”.

The Distant Choir comprises a unison chorus, horn, chimes, piano, harp, and strings. Removed from the main orchestra, they open the movement with the chorus intoning the Te Deum in English, the instruments playing what has been described as “background noise of New York rush-hour traffic.” The main orchestra enters, eventually subsuming the Distant Choir, but after a Gospel hymn is heard in full tutti they fade to leave the Distant Choir’s traffic noises again.

The work was not premiered until 11 February 1967 (by Morton Gould with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra), despite Ives writing the three movements in 1909, 1911 and 1915 respectively, later uniting the three programmatic pieces as one set.

Peter Laki has written on how the third movement commemorates the sinking of the Lusitania ocean liner by the German Navy on 7th May 1915. Laki refers to Ives’s Memos, in which Ives detailed how his experiences on the day of this disaster shaped the music.

“Some workmen sitting on the side of the tracks began to whistle the tune, and others began to sing or hum the refrain. A workman with a shovel over his shoulder came on the platform and joined in the chorus, and the next man, a Wall Street banker with white spats and a cane, joined in it, and finally it seemed to me that everybody was singing this tune, and they didn’t seem to be singing for fun, but as a natural outlet for what their feelings had been going through all day long. There was a feeling of dignity all through this. The hand-organ man seemed to sense this and wheeled the organ nearer the platform and kept it up fortissimo (and the chorus sounded out as though every man in New York must be joining in it). Then the first train came and everybody crowded in, and the song eventually died out, but the effect on the crowd still showed. Almost nobody talked — the people acted as though they might be coming out of a church service. In going uptown, occasionally little groups would start singing or humming the tune.

“Now what was the tune? It wasn’t a Broadway hit, it wasn’t a musical comedy air, it wasn’t a waltz tune or a dance tune or an opera tune or a classical tune, or a tune that all of them probably knew. It was (only) the refrain of an old Gospel Hymn that had stirred many people of past generations. It was nothing but — “In the Sweet Bye and Bye.” It wasn’t a tune written to be sold, or written by a professor of music — but by a man who was but giving out an experience.

This third movement is based on this, fundamentally, and comes from that “L” station. It has secondary themes and rhythms, but widely related, and its general makeup would reflect the sense of many people living, working, and occasionally going through the same deep experience, together…”

One last note about our performance: the unison chorus part of the Distant Choir will be sung by the main orchestra!